and

BLUE WHITE

the

Columbia University's Undergraduate Magazine. Founded 1890.

Current Issue

Current Issue

Campus Character

Illustration by Derin Ogutcu

Feature by Duda Kovarsky Rotta and Gabriela McBride

Illustration by Truman Dickerson

Illustration by Iris Pope

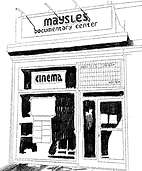

The Maysles Documentary Center keeps the spark of Harlem’s art film scene alive.

Feature by Caroline Nieto

Illustration by Selin Ho

Conversations

_edited.jpg)

Illustrations by Svea Van de Velde

In 2022, Blue and White staff writers Andrea Contreras CC ’24 and Briani Netzahuatl CC ’23 investigated the practical truth of the Columbia University as a 'sanctuary school'. Their article describes a university willing to publicly dissent against federal prejudice, while privately failing its undocumented students.

As federal hostility towards undocumented immigrants intensifies, revisiting 'The Search for Sanctuary' serves as a reminder of all that has changed, and what has stayed the same.

On creating community, by and for undocumented students.

Feature by Andrea Contreras and Briani Netzahuatl

Dec 12, 2022